Super 8: When Home Cinema was super...

We typically think that home cinema entered public consciousness with Blu-ray in the noughties, DVD in the nineties, or VHS in the eighties. However, owning and operating a personal screening room goes back a lot further. Well-heeled AV heads – think Hollywood moguls and glitterati – have been hunkering down in darkened rooms, adjusting comfy recliners, and kicking back for that special feature presentation since the early 20th century.

It was hardly a mainstream hobby, though. Before the first World War, hefty and expensive 35mm reel-to-reel projectors (as found in commercial cinemas) performed video duties in the home. The huge capital outlay for equipment providing such luxury meant the home screening room was a rare beast. Subsequently other more compact and manageable film formats jockeyed for position for home cinema supremacy.

But by the mid-1960s a revolution took place in the form of Super 8mm film. What had generally been the preserve of the wealthy – listening to the clatter of the turning sprocket wheels of a film projector, and beaming a catalogue favourite movie onto a living room wall – was a joy that the masses could now embrace. The worldwide leading manufacturer of Super 8mm projectors, Eumig of Austria, was producing over half a million such models a year by 1976, while punters increasingly reaped the rewards of a bigscreen experience to take on the underwhelming output of their small tellies. Collecting Super 8 films became an obsession for thousands of film devotees before the VHS era took hold.

For some enthusiasts, the magic of projected celluloid still hangs on to this day, similar to the audiophile passion for vinyl. And could we see a Super 8 renaissance of the type that vinyl has experienced? A couple of years ago it would have seemed unlikely, but Kodak rocked up to 2016's CES technology expo to showcase a new Super 8 camera that marries modern-day features (USB charging, 3.5in LCD swivel-mounted viewfinder) with recording to 50ft 8mm film reels. As part of its wider Super 8 Revival Initiative, the cam (pictured below) remains un-launched as yet, but Kodak earned approval from creative talents: 'While any technology that allows for visual storytelling must be embraced, nothing beats film,' said (director of sci-fi Super 8) J.J. Abrams. 'The fact that Kodak is building a brand-new Super 8 camera is a dream come true.'

Getting En-gaugedThe driving force for film projectors in the home was not only film collecting, but movie-making itself. The market for film formats less cumbersome than professional 35mm goes back to 1923 when Eastman Kodak introduced its ‘amateur’ stock: 16mm. Billed as a budget alternative for keen makers of silent films, the company touted its first outfit, consisting of camera, projector, tripod, screen and splicer, which could be snapped up for $335 (around $4,700 in today’s money).

The acetate base of 16mm film, as distinct from 35mm’s flammable nitrate base, made this new gauge appealing to household users. The ability to rent and buy commercial films from the Kodascope Library was a further boon. In 1935, optical soundtracks became available on 16mm stock, and amateur filmmakers, documentarians and news stations continued to adopt the format right up until the 1990s.

Another rather quirky film gauge (9.5mm) arrived on the scene in the early 1920s, this time from French powerhouse Pathé Frères. Introduced primarily for collectors of commercial movie titles, it did also gain favour with amateur content creators. Its slightly clunky single central sprocket hole mechanism made it a bit prone to print damage, though, and the arrival of Standard 8mm film in 1932 saw its appeal wane.

Also known as ‘Regular 8’, Eastman Kodak’s Standard 8mm film used side-mounted sprocket holes, identical in size to those on 16mm prints. Modified 16mm stock formed the basis of spools inserted into a Standard 8 camera, which needed removing and turning over mid-filming to render images down both sides of the exposable area.

Major studios began to release what became known as ‘package movies’ for collectors, but few were more than 200ft in length (about 8 minutes), and Standard 8 projectors with sound were rare.

Enter Super 8, Eastman Kodak's brilliant 1965 innovation which transformed the entire home movie industry. Smaller sprocket holes than Standard 8 allowed for a larger exposed picture area, and oxide stripes on both edges of the stock provided the means by which to record sound during image capture, or later during the editing process at home. Fujifilm, meanwhile, introduced its competing format known as ‘Single-8’. This Japanese challenger deployed a polyester (rather than acetate) film base, and its cartridge loading system required the use of proprietary licensed cameras for shooting, even though the final developed film would run fine in a Super 8 projector.

By the 1970s, Super 8 projectors at a variety of price points, and with a head-swirling range of feature sets, could be purchased from camera stores across the UK, with the bulk of the manufacturers hailing from Austria (Eumig), Germany (Bauer) and Japan (Elmo, Sankyo, Chinon), while Bell & Howell from the United States was also a major player.

By the end of the decade, anamorphic lenses were available for CinemaScope presentations of commercial releases, while two-channel stereo and Dolby Stereo exploited both magnetic sound stripes (the second designed originally for ballast as the film ran through the PJ).

Package dealsThe thrill of Super 8 was the wide selection of films available to collectors. Prior to the onset of commercial VHS tapes, there were literally thousands of film titles ready for purchase by mail order, or at retail stores peppered across the UK.

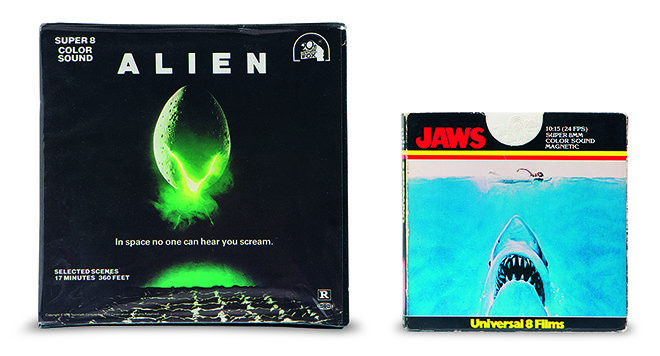

The most popular package movies were the 17-minute highlight reels (mounted on 400ft spools) of major titles, which the Hollywood studios released directly. A highlight reel would include a usually skilful edit of an entire feature film with beginning, middle and end intact, and usually cost £30 for a recent release. In 2016, it's a hard concept to get your head around, but consumers lapped them up. Want to relive the best bits from Steven Spielberg's Jaws or Ridley Scott's Alien whenever you desired? Now you could.

And Super 8 didn't die as soon as VHS appeared. Rather, as the VHS juggernaut advanced, Warner Bros., Fox, Disney and Columbia presented their celluloid titles in ever more alluring packaging, while Universal Pictures’ Universal 8 distribution arm pushed out a series of beautifully-transferred reels from its archive, housed in rugged injection-molded casings, and which included Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho and The Birds, disaster movies, and legacy horror.

Super 8 catered for all tastes, from the latest tent-pole Hollywood offerings to Harold Lloyd silent capers. Paramount Pictures even released full-length feature films on 6 or 7 x 400ft reels, including Grease, Saturday Night Fever and Marathon Man, while Dudley-based Derann Film Services specialised in full-length British greats from the Hammer vaults and Ealing Studios. Walton Sound and Film Services in London also provided a host of abridged and feature prints, mostly gleaned from the Rank catalogue. Price tags were usually north of £200 for a modern feature, so film collecting at that level was never a game for the faint-hearted.

Fade inNot everything is perfect about film. Colours fade over time, prints get scratched, the projectors are all noisy (and should be in a booth), and putting on a movie show is hard work. But if you’re even remotely repelled on occasion by the clinical sterility of your Transformers Blu-ray collection, then you might just be in the market for a film projector. The act of watching film in the home is utterly unique.

The hobby took a significant nosedive in the early 1990s before DVD arrived. That enthusiasts sat through demos of VHS tapes and LaserDiscs feeding £30,000 line-doubled and -quadrupled Barco CRT projectors, pretending they looked good while smiling politely, is extraordinary, particularly given that only ten years previously they'd thrown most 8mm and 16mm projectors in the bin.

I'd go as far to suggest no home cinema is utterly complete without a Super 8 or 16mm machine to sit alongside your Epson or JVC. Therefore, it's worth checking to see if older relatives have a film projector and selection of movies in their loft. A lot of these gadgets are still in existence. If you’re not getting any joy on that front, then check out the usual second-hand suspects online, or trundle over to the likes of Classic Home Cinema in Cleethorpes, where proprietor Philip Sheard, retailer of used film, projectors, and related paraphernalia, might just help you discover a world of untapped euphoria.

Why bother? Because this is about the romanticism of a bygone age, about being willingly hypnotized by the mechanics of a persistent turning feeder reel and take-up spool. For those old enough, it might bring up memories of watching B-movie double bills; all those things of which Quentin Tarantino was reminding us of in Grindhouse. It's an experience about analogue warmth and coziness, a gently meandering weave as the film passes through the gate, the sumptuous contrast and depth of field, and picture grain so dense you can bathe in it. The greatest AV travesty of the past 30 years has been the slow, miserable decline of film. You could play a part in keeping it alive!

|

Home Cinema Choice #351 is on sale now, featuring: Samsung S95D flagship OLED TV; Ascendo loudspeakers; Pioneer VSA-LX805 AV receiver; UST projector roundup; 2024’s summer movies; Conan 4K; and more

|