King of the monsters! Celebrating more than 50 years of Godzilla

In the early 1950s, inspired by the successful Japanese re-release of 1933's King Kong, and the subsequent international debut of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, Tomoyuki Tanaka, a veteran producer at Japan's Toho Co. Ltd studio, had the idea of creating his own epic monster flick. Originally developed under the derivative title The Beast from 20,000 Miles Under the Sea, the film was eventually named after its giant creature as Gojira – a portmanteau mixing the Japanese words for gorilla (gorira) and whale (kujira).

Where Hollywood’s monster movies had typically been more concerned with spectacle than anything else, Godzilla (the Toho-approved Anglicised title) drew heavily on recent Japanese history. Many have discussed the monster's destructive rampage in the context of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II, but more direct inspiration was taken from a different event: in 1954 a Japanese fishing vessel – Lucky Dragon 5 – was exposed to radioactive fallout from a US hydrogen bomb test. The crew were treated for acute radiation sickness (all but one survived), yet some of their irradiated catch made it to market, sparking a national crisis. The incident is directly referenced in Godzilla, in an early scene where the radioactive reptile attacks a fishing boat.

The design of the titular creature went through numerous iterations (including an overgrown octopus and a beast with a head shaped like a mushroom cloud), until the production team settled on a combination of several dinosaurs. Special effects chief Eiji Tsuburaya was a fan of American stop-motion animation legend Willis O’Brien (The Lost World, King Kong), and hoped to use the same technique to bring Godzilla to life – an idea that was rejected once he told producers it would take about seven years to complete. Instead, Tsuburaya created a rubber monster suit over a bamboo and wire mesh frame, for a performer to wear while smashing around meticulous scale models of Tokyo Bay and the movie's other locales. An icon was born...

From villain to hero

Directed by Ishiro Honda, Godzilla triumphed at Japanese cinemas, grossing 183m yen and nabbing the number eight spot on the list of the biggest box office hits for 1954. In the process, it essentially spawned a new entire genre, that of the kaiju (strange monster) movie. But how did it go from there to a franchise awarded the Guinness World Record for the longest continuously running film series in history? The answer lies in its ability to continually evolve and change.

Toho’s Japanese Godzilla films are split into four eras – Showa (1954-1975), Heisei (1984-1995), Millennium (1999-2004) and Reiwa (2016-present) – each of which has its own distinct approach. And within these there have been differences in how Godzilla is represented, something particularly apparent in the two-decade span of the Showa era.

The original Godzilla was played straight and took its subject matter very seriously; by the third film in the series (1962’s King Kong vs Godzilla) there was much more humour, with the monster brawls even borrowing moves from the world of professional wrestling. And although there would still be ‘serious’ Godzilla films, an awareness of the creature’s popularity with younger viewers led to a softening of the character. For instance, 1967’s Son of Godzilla featured Big G’s offspring, a cute creature dubbed Minilla that could only blow smoke rather than breathe radioactive fire.

These weren't the only changes the franchise underwent during the Showa era, with more science-fiction elements introduced throughout the '60s and '70s. 1965’s Invasion of the Astro Monster (aka Monster Zero), 1968’s Destroy All Monsters, 1972’s Godzilla vs Gigan, 1974’s Godzilla vs Mechagodzilla and 1975’s Terror of Mechagodzilla all involve alien invaders either taking control of Earth’s giant monsters or unleashing ones of their own.

More important, though, were the tweaks made to Godzilla himself. Originally conceived as an unstoppable destructive force, by 1964’s Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster he was learning how to play well with others, teaming up with former foes Anguirus (a mutated ankylosaurus) and Mothra (a giant moth which had its own solo film in 1961, before being pitted against Godzilla three years later), to battle an extraterrestrial menace. And by 1971’s Godzilla vs Hedorah (aka Godzilla vs the Smog Monster, aka Godzilla vs the Thing) he had officially been repositioned as a defender of the planet, restoring an ecological balance by battling a monster that was the living embodiment of pollution.

Coming to America

For the arrival of 1984’s The Return of Godzilla (aka Godzilla 1985), producer Tomoyuki Tanaka took the franchise back to its roots, ignoring nearly everything that had gone before and returning Big G to his original role as a living natural disaster. The theme of nuclear war also returned, thanks to the film’s Cold War backdrop. Tried and trusted ‘suitmation’ techniques continued to be used, but the quality of the monster suits and the miniature work was now leaps and bounds ahead of what had been seen in the Showa era.

Preferring a slightly more ’real-world’ approach (at least, as much as you can with a series of films about giant monsters), the seven Heisei era films jettisoned the goofy humour of earlier movies, keeping in step with the new breed of Hollywood blockbusters that were dominating the international box office. In fact, you only have to take a look at 1991’s Godzilla vs King Ghidorah, with a plot involving time travel and a Schwarzenegger-esque cyborg, to see precisely how much of an influence contemporary US action films were having on the Japanese franchise.

However, Godzilla had also become popular with American audiences. A combination of theatrical releases and regular play on cable TV networks throughout the 1970s meant a generation of Americans had grown up with the Showa movies. Animation powerhouse Hanna Barbera tapped into its popularity, producing a kids’ cartoon series that ran for two seasons between 1978 and 1979. It's now best remembered for its catchy theme song (‘Up from the depths. 30 storeys high. Breathing fire. His head in the sky…’) and for giving the world Godzilla's comic-relief ‘cowardly nephew’ Godzookie. While unavailable on Blu-ray, it can be found on Region 1 DVD.

At the same time, Marvel Comics was publishing its own Godzilla comic book. Across 24 issues, from 1977 to 1979, he battled various monsters and even had run-ins with Nick Fury’s agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., the Fantastic Four and the Avengers. Such was the creature's recognition factor, it went one-on-one with a giant-sized version of NBA star Charles Barkley in an infamous 1992 Nike advert (which spawned its very own one-shot comic).

So it didn’t come as a surprise when a post-Jurassic Park Hollywood began to take an interest in the deadly dinosaur.Following false starts that had James Cameron, Tim Burton and Jan De Bont courted to helm the project, 1998 gave cinemagoers Roland Emmerich’s Hollywood remake, simply titled Godzilla. Unfortunately, neither Emmerich nor his co-writer Dean Devlin appeared to be fans of the Japanese films and reimagined the character and its design, preferring a smaller, faster, mutated iguana that looked more like an escapee from Jurassic Park than the iconic movie monster (leading to franchise fans to dub the creature GINO – Godzilla In Name Only). While it grossed around $380m worldwide, Godzilla was considered a flop and Columbia TriStar’s plan for a couple of sequels was quickly dropped – although the film did spawn a well-regarded two-season animated spin-off (Godzilla: The Series, 1998-2000).

It wasn’t Godzilla’s first brush with US filmmaking, though; the original 1954 movie had been completely overhauled for its 1956 US release (under the title Godzilla, King of the Monsters!). As well as cutting much of the political and anti-nuclear material, 16 minutes of brand-new footage were shot featuring Raymond Burr as an American journalist, commenting on the action and sometimes even interacting with the main cast (using body doubles). When Roger Corman’s New World Pictures picked up The Return of Godzilla for a US release, under the title Godzilla 1985, a similar thing happened again, with Raymond Burr returning (presumably funded by Dr Pepper, given the blatant product placement). Despite this, the US re-edit still runs quarter-of-an hour shorter than the Japanese version.

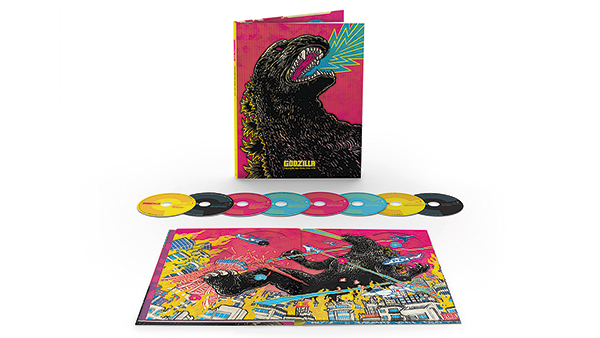

Perhaps the most annoying US do-over is that of King Kong vs Godzilla, which again cut chunks out of the original film and padded it with new footage of an American journalist, but also added stock footage from other films, and replaced Akira Ifukube’s score with library music from other US monster flicks. Until recently, this remained the only version of the film to have ever been given an official release in the UK or the US – until Criterion Collection's Godzilla: The Showa-Era Films, 1954-1975 Blu-ray boxset arrived.

Going home

Presuming that Hollywood would be taking ownership of Godzilla, Toho killed the creature off with the final film of the Heisei era, 1995’s Godzilla vs Destroyah. Picking up story ideas left over from the very first Godzilla, this surprisingly moving film thrusts concerns about nuclear energy to the fore as Godzilla’s radioactive core goes into meltdown, threatening not just Japan but the entire world. Yet, with Roland Emmerich and Hollywood dropping the ball, Toho brought Godzilla back home, embarking on a series of six essentially standalone films (the one exception being 2003’s Godzilla: Tokyo S.O.S., a direct follow-up to the previous year’s Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla).

Although these films (known collectively as the Millennium era) once again tried to keep pace with Hollywood cinema by foregrounding action above all else, they didn't entirely abandon serious thematic concerns. The most interesting is 2001’s sensational Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack, which ignores Godzilla’s nuclear origin and instead reimagines the creature as a vengeful supernatural force powered by the spirits of those killed during the Pacific theatres of World War II. But one clear downside of trying to keep up with US cinema is the proliferation of poorly rendered CG effects, which prove far less convincing and believable than the ‘suitmation’ techniques they sit alongside.

The Millennium era films fell short of the studio's box office expectations. Toho again decided it was time to put the series on ice. It would have one final blow-out with 2004’s Godzilla: Final Wars, a madcap mash-up from Ryuhei Kitamura, director of the ultra-violent zombie hit Versus, that harks back to the silliness of the Showa era films and even pits the real Godzilla against his recent US counterpart – albeit in a fight that lasts all of 20 seconds (suffice to say, it doesn’t end well for the CGI pretender).

A legendary reboot

As the films have shown, though, Godzilla is nigh-on impossible to kill. It wasn't long before he was stomping the silver screen once more, and the next rebirth came from a particularly unexpected source: Yoshimitsu Banno, director of the wonderfully weird 1971 outing Godzilla vs Hedorah. First, Banno convinced Toho to grant him the rights to make a 3D IMAX Godzilla movie, called Godzilla 3D to the Max. However, his plans grew more ambitious and eventually led him to the door of youthful US production company Legendary Pictures, which had made a name for itself with Batman Begins (2005) and 300 (2006). Banno ditched the IMAX idea and instead acted as an intermediary between Legendary and Toho about obtaining the US remake rights.

The result was 2014’s Godzilla. Directed by Gareth Edwards (who had prior kaiju experience with his 2010 debut Monsters), this was a smart and stunning piece of blockbuster cinema that – unlike the 1998 effort – captured the spirit of the source material, while also giving it a specifically US spin through its focus on military heroism. And again Godzilla underwent an evolution, becoming the lynchpin for a shared universe of monster movies (the MonsterVerse), kicking off with 2017’s Kong: Skull Island, followed by this year’s Godzilla: King of the Monsters, and 2020's Godzilla vs. Kong.

The international success of the US film spurred Toho on, although the next Japanese Godzilla movie would showcase a total reinvention of the creature. Co-directed by Hideaki Anno (of Neon Genesis Evangelion fame) and Shinji Higuchi (director of the live-action Attack on Titan films), 2016’s Shin Godzilla featured a horrifying, rapidly mutating take on the title character, and mined a vein of black humour with its focus on Japanese bureaucrats struggling to battle through red tape in order to deal with the unfolding crisis. The film also updated its historical sources, making clear reference to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and the Fukishima nuclear power plant disaster. A huge domestic hit, Shin Godzilla grabbed the Picture of the Year and Director of the Year awards at the 40th Japan Academy Prize ceremony.

Yet with a contract restriction in place saying that Toho cannot release any live-action Godzilla movies in the same year as Legendary Pictures, and with those US rights due to expire in 2020, the Japanese studio has yet to reveal its future plans, beyond confirming that whatever emerges won’t be a direct sequel to Shin Godzilla. It will instead kickstart its own new shared universe of monster movies. In the meantime, though, Toho has financed a trilogy of animated films for Netflix (2017’s Godzilla: Planet of the Monsters and 2018’s Godzilla: City on the Edge of Forever and Godzilla: The Planet Eater), which took things in yet another direction.

For the moment, then, Godzilla continues to slumber in his homeland. While you wait for his reappearance you can continue to revisit previous cinematic outings, catch up with the latest US release – Godzilla: King of the Monsters – read about him in comic books (still going strong today, thanks to IDW Publishing) or play with the many toys and collectibles. And if none of that completely scratches your G-fan itch, make a pilgrimage to Tokyo’s Hotel Gracery Shinjuku, where you can wake up to the sight of a life-size Godzilla starring into your window, courtesy of a 12-metre tall roaring replica of the legendary monster’s head installed on the eighth-floor terrace...

|

Home Cinema Choice #351 is on sale now, featuring: Samsung S95D flagship OLED TV; Ascendo loudspeakers; Pioneer VSA-LX805 AV receiver; UST projector roundup; 2024’s summer movies; Conan 4K; and more

|