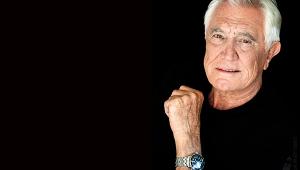

Neill Blomkamp: fan-fave director on shooting new movie Demonic in the midst of the pandemic – plus his love of RoboCop and Alien

The helmer of District 9 and Elysium’s first feature foray into the horror genre, Demonic tells the story of a woman (played by Carly Pope) offered the chance to use experimental technology to enter the mind of her comatose mother, only to unleash a terrifying supernatural force.

In advance of Demonic's arrival on UK Blu-ray and DVD, we chatted with Blomkamp about the freedom that low-budget filmmaking offers, and his thoughts on the future of cinema.

Was Demonic an idea you’d had for a while, or was it born out of

the situation the world found itself in last year?

It was born out of it, for sure. I think the only thing that kind of existed before was [...] wanting to do something with this idea of a virtual reality environment, with someone that is in a coma. So that was about it.

When everything shut down we were kind of looking at a Paranormal Activity or The Blair Witch Project approach to self-financing something in the woods for fun. It was a case of rummaging through older ideas and I think the simulation one was the only one that stuck. And then we just created everything else. As we knew what locations we could get and what actors we could get, we just sort of formulated it around them.

Your previous features have been sci-fi with elements of horror.

This is your first horror film, albeit with elements of sci-fi.

Are you a fan of the horror genre?

I don’t like gore horror, torture porn horror. But I really like films like The Shining or The Exorcist. Alien is an interesting mixture of both [genres].

So I think probably, over time, more science-fiction films have had an effect on me than horror, but the ones that have had an effect on me, I really, really resonate with.

I think at some point it would be fun to make a fantasy film, too. All of these fantastical genres are pretty interesting.

How difficult was it to set up a new film during the pandemic? Did you get pushback from people who thought there was no point trying?

Yeah, we got a little. Overall I wouldn’t say it was that bad, but we got a bit of pushback from a couple of people – that was a bit surprising to me. But I don’t think it was that difficult. We were so early at the beginning of the pandemic [shooting began in early Summer last year] that we had to figure out what the protocols and rules were for how to shoot

a film – [it's] way more defined now.

I’ve always loved how the filmmakers behind Blair Witch… and Paranormal Activity just went out and used things they had access to. It’s a very creative, awesome thing to do. And it was the perfect time to do it, because everything else was paused.

So, once I decided that’s what I wanted to do, the goal – on a creative level – became how to try and create as much of a sense of brooding dread, this simmering layer under the movie of dread, that was there all the time. Even though locations we were shooting in were sunny, on purpose, I wanted this feeling under it of unsettled evilness. That was the primary goal. Every choice I made was based around reinforcing or coming back to that idea. It just snuck in there and lay under the surface of the movie.

Shooting a film during lockdown must have brought challenges...

We had one crew member who got sick and we had to shut down production until their test results came through – and that has pretty dramatic effects on the way it knocks the schedule down, because then you lose locations. But that was the only actual Covid hiccup that we had.

The only other random thing, that was kind of hilarious, was that we had this sanitarium location at the end of the movie and it was infested with rattlesnakes. That was pretty funny. We had a rattlesnake wrangler on set. That caused some concerns with the crew.

How did you handle location scouting and casting during the pandemic?

Location scouting depended on where you were going and how people responded. Certain locations were way more fearful and really made us do a lot to make sure they felt okay, while other places were more… lenient, I guess. But, ultimately, we just followed whatever protocols we were given and got stuck into it.

In terms of casting, I’d worked with Carly [Pope] on some of the Oats pieces that we did and I worked with her a little on Elysium. I felt she would be awesome on several levels, her talent level and her willingness to get down in the weeds with something that would be a low-budget production. Because you need the right kind of soldiers around you.

So before the story was even fully formed, I knew I wanted to work with Carly, she would make for magnetic viewing. Kandyse [McClure] and Terry [Chen] were both results of Carly’s influence, which was pretty cool. And Michael Rogers I’d worked with before. So really it was a case of assembling a group of people I felt I wanted to work with. It wasn’t a case of casting like normal, auditioning. I didn’t do that.

Did you enjoy the relative freedom of a low-budget, guerrilla shoot? Are you inspired to make more features along these lines?

Oh, totally. One million per cent. I mean, I’ve spent the last four years making YouTube videos, so I have zero qualms about working with a lower budget.

I actually love it. I think the key for me, at least, doing everything I want to do, is oscillating between high-budget and super down-and-dirty low-budget. It’s about finding ways to be creative. Maybe it’s not even in film.

How difficult was it to get the look of Demonic's virtual reality simulations – that balance between glitchy computer imagery and something more real?

I was saying that there was one element that came from before the pandemic that I wanted to put in. That simulation concept was predicated on the idea of using relatively cutting-edge technology called volumetric capture. It’s kind of like what audiences would know as motion capture, where the motion of an actor’s body and face is recorded and applied to a three-dimensional object. [But] volumetric capture isn’t that. It’s like three-dimensionally capturing a stage play. So your actors are in hair and makeup and wardrobe. It’s holographic video, essentially.

So those glitches are… I knew that they would be in there and I knew that the only way to justify it, using volumetric capture, would be something like a glitchy simulation. You’d have to write it narratively into the movie; there’s no way we could fix those glitches. So it’s an aesthetic choice only in that I knew it would look that way. There was no aesthetic modification once you bring that into visual effects.

And then we treated the environments they are in the same way. So the childhood home or the sanitarium, these places that appear in the simulations, we gathered that information the same way – thousands of photos. The computer extrapolates a three-dimensional object. And then, instead of making it perfect, we purposefully left in the glitches that would marry together with how the video portion of the actors looked.

The film’s demonic entity manages to avoid rehashing something we’ve seen before, while still retaining the feel of something from recognisable folklore. Where did the design come from?

That was honestly probably the easiest design job I’ve ever done on any film. I don’t know why I wanted it to look like a crow, I’m not sure. My theory is, because of everything related to the pandemic, in the movie I have that [plague doctor] pandemic mask from the Middle Ages, and there’s something beak-like about that mask that I think led to the whole anthropomorphic raven idea. I don’t know. But I knew it was like a seven-foot raven, basically.

There’s this amazing concept artist that I work with, Eve Ventrue. She got my write-up of the creature and sent me an illustration that was essentially 100 per cent bang-on immediately. So I wrote it really easily, she illustrated it first round, and it was just done. It crossed my mind that the audience would think it looked goofy with its giant beak. But I knew also that there was a possibility that it would look terrifying. So I was like ...let’s see what happens.

Did you spend time in lockdown watching films like the rest of us?

Yes [laughs]. It’s more movies than bingeing TV shows. But I watched a lot of stuff. I’m just trying to think what really stood out for me… I definitely binge-watched a lot of films.

Do you have a home cinema setup?

Kind of. I moved away from Vancouver to the house we’re in now. It’s not a dedicated theatre room like before, but it’s pretty good. It just needs a bit of work to be dialled-in properly.

Your previous films (District 9, Elysium and Chappie) have all

been released on Ultra HD Blu-ray. What are your thoughts on 4K HDR as a filmmaking tool and a home entertainment medium?

I think it’s amazing. There’s obviously nothing but good things about it.

My – I don’t think it’s a concern – [but] it seems like an impossible march towards home theatre and away from the cinema experience. I’m curious just what that means and what that’s going to look like. Because obviously, as a filmmaker, the big audience experience is my favourite, even though I’m such a fan of watching high-resolution, amazing stuff at home; a massive super hi-res TV or projector. What I wish is that it’s the best of both worlds, where theatres exist and people go and watch movies in theatres, and then later watch them again at home.

For everything that’s positive about 4K and high dynamic range, the issue is that I don’t want theatres to die. And it feels like they won’t, but I don’t know in what way they’re damaged. It feels like what’s going to happen is the theatrical experience is going to gravitate more towards the theme park ride of it all. That’s the experience they can give you. It’s like $300m-400m films with borderline zero character development and just dangling lava and explosions. It’s like you’re going there to witness a rollercoaster kind of event. And then, for everything else with subtlety it’s longer-format, at-home viewing.

And maybe that’s fine. But I wish there was a wider breadth to the movies that will still be released in theatres. I feel like there’s going to be fewer theatres and fewer movies released that will be bigger. It’s some form of that equation, I think.

Talking about big franchises, although your features to date

have all been original ideas, you were involved in developing Alien and RoboCop sequels. They didn’t come to fruition, but what was it about those franchises that appealed to you?

Oh man, I could talk for hours about the elements that are appealing about those two different franchises. What Ridley Scott did – and then what James Cameron amplified – with Alien is really amazing on multiple levels. It’s such an incredible grouping of ingredients. You've got this kind of weird Freudian psychosexual stuff related to Giger’s alien, and the horror-ness of that combined with the character of Ripley, and combined with the design aesthetics of this off-world far future, whether it’s the Nostromo or the Sulaco. It’s just highly, highly interesting.

And RoboCop… I don’t now why I’m obsessed with body horror and body mutation and man-machine merging and stuff, but the loss of human-ness with Peter Weller, and the corporatisation of, you know, cutting a person up, is highly interesting too. Those two franchises are fascinating.

And are there any other existing properties that you’d be interested in taking a crack at if the opportunity presented itself?

The way my brain goes with it is that there are so many inherent rules and regulations about how these properties have to be interpreted that it feels more beneficial to me to just work on original stuff. Because I think that if you bring truly original stuff to IP [intellectual property], firstly the studio wouldn’t be that happy, and there’s a possibility that the audience wouldn’t be happy.

But, then, there’s something to be said for… the way I was going to do RoboCop was to emulate [original director] Paul Verhoeven as best I could. Which is completely different from how I would have done Alien.

RoboCop would literally have felt like a sequel that began the morning after Dick Jones had fallen onto the sidewalk. That’s my approach. The only thing that we would have had to have done is to digitally de-age Peter Weller. So that was a case of emulation, in a way that the audience would have gotten more of RoboCop the way that it appeared in 1987. But that’s the only project that I’ve thought that way about.

Alien would have been my own in the way that all of the other filmmakers that worked on [the franchise] made it their own. And anything else that I do, my assumption would be that it’ll be my own.

Neill Blomkamp’s Demonic is out on Blu-ray and DVD via Signature Entertainment on October 25.

|

Home Cinema Choice #351 is on sale now, featuring: Samsung S95D flagship OLED TV; Ascendo loudspeakers; Pioneer VSA-LX805 AV receiver; UST projector roundup; 2024’s summer movies; Conan 4K; and more

|