Exclusive Interview: Re-master class

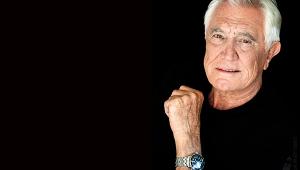

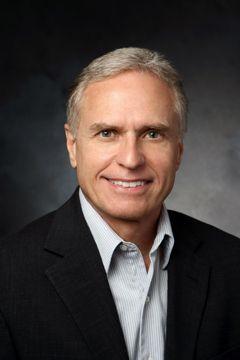

Senior Vice President, Asset Management, Film Restoration and Digital Mastering, Sony Pictures Entertainment. Grover Crisp's job title doesn't sound particularly exciting. Yet this affable American has one of the coolest jobs in home cinema, overseeing the Blu-ray releases of everything from classic films to the latest 3D blockbusters. With the Blu-ray release of Taxi Driver and The Bridge on the River Kwai on the horizon, I sat down with Crisp to discuss remastering these two Hollywood classics...

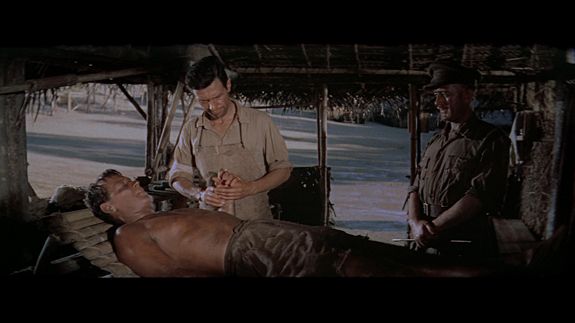

You've recently finished a Blu-ray restoration of The Bridge on the River Kwai...

'Well, what’s interesting about this film is that the studio did a restoration I was not involved in about 20 years ago. It was entirely photochemical and it was okay for its time. There were a lot of things that they couldn’t do then. About ten years ago, for the first DVD we wanted to release, I did a little more follow-up, and we did some new mastering at that time. And it was actually then that we discovered so many issues with the film materials. Things that were actually quite evident when you look at the print, but which tend to get buried as you collapse the resolution down from film or HD down to standard definition.

'So, when it was decided that this would be the next David Lean film to come out on Blu-ray, which was about a year ago I guess, I decided it was time to start working on it the way we’ve been doing a lot of our other restorations latterly. So we went back to our original negative, we did a 4k scan of that and we kept the entire work flow at that level all the way through. And I guess it was about a good six months’ solid work, every day work.

'The issues with the film are fairly traditional in terms of damage and deterioration over the years – torn frames, things like that, scratches, there were scratches that ran for hundreds of feet in every single reel of the film. Those proved very problematic of course. One of the reasons for that is the original aspect ration is the original Cinemascope ratio of 2.55:1 and those scratches were right in the middle of the extra footage when you frame it properly. So that was time consuming and challenging.

'More challenging however where the inherent issues with the production; there was a camera problem - and clearly this was a Columbia-owned camera, because studios owned their own cameras for a long time - and one of the problems with this film we’ve also noticed with a lot of other Columbia Cinemascope films from the same period. It’s a bit of a jumping in the image, which is actually in the camera, so if you were to watch a print directly off the negative you would see this little jump from side to side, as well as some misregistration where edges of characters seem to suddenly bloom out in the back. At first we thought this was just some colour-fringing, but it became clear that it was a camera lens issue. Those problems ran throughout the entire film. And you’re kind of forgiving of things like that when you watch a print, but in high-definition for Blu-ray, it’s pretty unforgiving. So we decided that we needed to try and deal with those issues as best we could. And we spent a long time doing a lot of digital clean-up for those kinds of issues. It wasn’t terribly faded though, so the colour actually looked pretty good'.

'Our goal with this, as with everything we work on, is that when we do it digitally we still try to maintain the film look. It has to look like a film. Not necessarily a film made today, but certainly as if it were new in the period when it were made. So we didn’t really do anything with the grain or anything like that. And I feel that if you treat it correctly in terms of your scanning and your resolution to work at, some of those kinds of things take care of themselves'.

Which brings us nicely to that ever-present Blu-ray bogeyman Digital Noise Correction...

'I really take the phrase home cinema very seriously and the whole idea behind that concept – especially when DVD came along and everyone suddenly started outfitting their rooms and literally creating home theatres – is that you want to replicate that experience you had in a motion picture theatre. So, rather than looking at a big video presentation, you want to look at a cinema presentation. That’s our operating mantra, so to speak, to try and maintain the original look and feel and sound of film'.

Were you able to get anybody who originally worked on the film to advise in the restoration?

'There was one cast member alive - Geoffrey Horne who gets an introduction credit on the film. I haven’t met him yet, but he’s supposed to be coming to a screening in Washington DC next month, so we’ll see if he makes it.

'I work with a lot of cinematographers on their films if they’re still around and are willing to come in. We embrace that because cinematographers really know how their films should look. But Jack Hildyard is no longer around and David Lean is not around. We had reference prints and also, because of the issues with the film, at a certain point the film itself tells you where to go, you can only push it so far in one direction or another whether you do it photochemically or digitally, like we did this one'.

Ironically, it seems that every fan posting online these days is a restoration expert with elephantine memories of what the colour timing was like in a film they saw on its original run some 40 years ago.

'That is interesting that concept. I co-ordinate a technical symposium a couple of times each year. We did one in Los Angeles last August with a lot of presentations revolving around new technologies for preservation and restoration. At one screening there was a famous cinematographer sat in the theatre at the time and he said, "Well, this film doesn’t really look the way I remember it when it was new". So, when I got back up to the microphone I said, "When this was new it was 1958! And you’re telling me that you remember exactly how it looked, when you must have been about eight- years old at the time" and he didn’t really have an answer for that. But our memories are… you know, it’s kind of like when you were a kid and you went to your grandparents’ house and the living room just seemed like this huge, vast canyon or something. Then you go back when you’re an adult and its just like "Wow, this room is a lot smaller than I remember". Our memories play tricks and so I never trust that.

'The other point that I made in that exchange I had is that there’s not a film at all today that’s going to look the way it did when it was originally released 30, 40, 50 years ago. Partly because the characteristics of the physical film itself changes over time. Also, film stocks are different now, so you get a different colour curve out of it. The processing is different as well – the optics in the film printers are different, so a film printed now off the camera negative versus a film printed off the camera negative in 1945 is going to look somewhat different. It’s going to look sharper for one thing now, because the optics are sharper. The grain is going to look different on the print because the grain is different in the new film stock. I mean, there are just so many things that are different that it’s never going to be exactly precise.

Absolutely. It pts me in mind of the Ray Harryhausen films you’ve worked on, like the superb Jason and the Argonauts Blu-ray. They’re a great example of the impact of optical effects on picture quality.

'On that film, when it came time to look at the optical effects in that for the Blu-ray, I actually called Ray up and said, "In the Harpy sequence, I’m thinking that we might remove the wires, do you mind?" and there was a pause and I’m thinking he gonna say, "You can’t touch my film!". Instead he goes, "What wires?". So I said that it was the wires that are holding the Harpies. And he goes, "But you can’t see those" and I had to tell him, and this takes us back to high-definition, that you can in this environment. In a print it’s a little bit buried, but not now that we’re working in a digital environment. And he said, "Oh, by all means, remove them", because you’re really not supposed to see them. And that was the only concession we really took, and I took it only after getting the advice of the creator of the film.

'But that seems to be pretty much what all filmmakers say. Like Spielberg on Hook. He wanted all of the wires removed from Tinkerbell. And even on a Terry Gilliam film that we’re working on, he came in and the first thing he said was ‘Can you remove the wires?’. And it’s all about maintaining the illusion, so I get that'.

Going back to Bridge… what size team did you have working on that?

'We did the work at our new ColorWorks facility, which is a digital intermediate facility for finishing our new titles – Salt was done there and the new Karate Kid. But it’s also a mastering facility and a restoration facility. So digital film restoration really is basically like a DI, it’s the same kind of concept – we scan the film and work on it in a high-level digital environment. We did the core of the work there, we outsourced a lot of the clean-up to company called MTI Film in Los Angeles, and part of that was because it was really labour-intensive and we have a schedule to meet, and a lot of work was also done internally with restoration artists, graphic artists. That was the lion’s share of the work.

'I worked with our colourist Scott Ostrowsky, and the funny thing is he and I had worked on this title back some years ago, about six years ago, when we were just doing an HD transfer, so it sort of fit that we got back together and did this since he now works at Colorworks. So that was it, we kept it at 4k, we scanned it… every day I would go in with him and we would sit and look at it in a huge theatre on a big screen, which is the right way to do it, and tweaked the colour a lot to match where we thought it should be'.

And would you say that 4k is the optimal resolution for producing hi-def masters for Blu-ray?

'We switched over when Blu-ray started to flourish about three years ago. Instead of just doing a film to HD tape transfer, we actually scan it at 4k. It doesn’t matter what the film is or what the title is, the scanning is the most important part – if it’s a high enough resolution it helps the grain management for example, you don’t really have to do any noise reduction. There may be some selective things like that that everybody does now and then, but for the most part it helps manage that. And that is essentially the basic resolution of film. If it’s a large format, 65mm, we may scan it at 8k just to make sure we've captured everything'.

Catalogue seems to be proving a harder sell on Blu-ray than it ever was on DVD, do you think that’s simply down to a lack of consumer education about what the format does for older titles?

'We’re working on putting together some examples. One is with The Bridge on the River Kwai, just to show once again the difference between DVD and Blu-ray. We’ve created some split-screen examples, literally pulled off the discs, just to show. At the studio we have a showcase room and invite journalists and technologists in to show examples of this thing. I don’t really have an answer though.

'What we’re really excited about is being able to get as many of the classics out on Blu-ray as we can. It’s a little bit slow going, but sometimes the work is slow. Lawrence of Arabia will be a long process, because it has a lot of issues like this film in terms of damage to the original negative. And this is actually the first time the original negative has been used since the restoration that was undertaken some 20 years ago. Even then they just printed off it to make an element and never went back to it again. So all the prints that have ever been made for that film from that restoration are actually from a duplicate negative. And that work was good for it’s time. But there are a lot of things we can do now that, again, no one could do 20 year ago, no one could do ten years ago. So we’ll get there'.

Taxi Driver is also arriving on Blu-ray this year. With this, the issue of grain retention is vital. In my head it's a film that's both gritty in theme and texture.

'It’s very interesting you say that, because just the other day we had the cinematographer Michael Chapman come in. We’d been working on it for a few weeks and it was now ready for him to come in terms of colour, density, you know, making sure it looks the way it should look based on the fact he shot the film. And what is interesting going back to the negative and working off of that is that we had this conversation while we were watching the film. He was really happy with how it looked, but I said to him, "You know, a lot of people just think this is this really grainy, grungy film in terms of the way it looks. But it’s really not that grainy". And he said, "I know. I think it’s because of the theme that everyone thinks it’s this grungy, dark film". But it’s actually pretty crisp and sharp looking for most of it.

'The opticals, and there are lots of them, are traditional, but they’re pretty well done. Not like in Bridge… which were all done really poorly. That was a huge challenge for us, because they were just not well done at the time. But they were pretty well done in this film. So its reputation as being overtly grainy is not what you’ll see when it comes out. And we’re doing absolutely nothing to the grain. It is what it is.

'But it’s a great film. It’s still a shocking film. It is actually quite amazing to listen to some of the dialogue and realise that 35 years have passed and it’s still pretty shocking in places. But it’s absolutely a great film I think for its time and especially in its place… you know, New York is a whole different city now than it was then. And a lot of places actually in the film are literally gone, they don’t exist. The cafes where they meet, the diners, some of the streets with the buildings in the back, they’re just gone. So it’s interesting from that kind of historical perspective.

'Also, Taxi Driver will look different than it does on the existing DVD edition. The last time it was remastered was about 2002, I think. So every version that has come out since then has been sourced from that restoration. When we started working on Taxi Driver from the negative, we had the previous master as a reference the whole time and I also had an answer print from the original negative approved by Marty and the cinematographer. So we knew how that should look. What we discovered was that the old master had compromised the film in a number of ways. They had blown up the image to avoid things like changeover cues to avoid painting them out. They reframed it from where it should be based on the 1.85:1 SMPTE [Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers] specifications. The "you takin’ to me" scene, for example, was seriously cropped on that edition. The shots were originally from the camera looking at his reflection in the mirror, not straight on of him while he talks, but they had cropped out the side of the mirror to give him more headroom, but you could barely see the gun he’s holding'.

What about the desaturated colours in the film’s finale originally insisted on by the MPAA, did you ever consider putting those back to how they were shot?

'We discussed it, but the film wasn’t just printed darker or muted as some people think. The two sections were actually cut from the camera negative and sent to a small lab in New York where it went through a Chemtone process that opens shadows allowing for greater density and lower contrast. They delivered back duplicate negatives of the two sequences, in effect an optical dupe with the desired colour and density built into it. We’ve searched many times over the years for the original negative they were sent, but have never found it. Most likely it was junked at the time.

'So those muted colours are built into the dupe negative and there is no way to grade it or print it the way it was originally shot. You can’t succesfully pump colours back into a film that aren’t there. There have been attempts over the years, like the old DVD, but the colours were not right. The extra red in the sequence is everywhere, in the walls, clothing, skin, everywhere. And we talked to the cinematographer about this, and it’s like, ‘Well, which way is it supposed to be?’ And his answer was that we should follow the film. So the colour in a number of scenes when it comes out on Blu-ray, especially the last reel, will be quite a bit different from what it was when it came out on these DVDs and is more accurate to how it looked in 1976. That’s one of the great things about Blu-ray, you can get it more accurate'.

With that in mind, what are your thoughts on what William Friedkin did with The French Connection, where he completely changed the colour timing for the film’s Blu-ray release?

'I’m friends with Owen Roizman, who shot that film, and we’ve talked about it a number of times. He’s been pretty outspoken about it, but even Owen agreed that at the end of the day it is a director’s medium and it is Friedkin's film. The only thing I think about things like that – and I must say, there is an analogy with old photochemical-type restoration versus what we can do digitally – is that if you are going to alter it that way, it’s got to be a creative choice, it’s got to be the filmmaker. These films may belong to us from a business perspective, but the creative aspect is the filmmaker’s. So it’s not up to us to impose our own aesthetics on a film, it’s our responsibility to whatever it was that was done. So if a filmmaker does that, that’s one thing, and I suppose that’s their prerogative. As long as the original is also maintained somehow, so it’s still, from a historical and cultural perspective, it’s still available'.

In a way that’s like some of the Harryhausen titles on Blu-ray. Where he was involved overseeing colourisation of the films, but the discs also include the original black and white versions.

'Yes, we insisted that we be able to make both available, which Ray was fine with. And Ray had said that they would have made them in colour at the time if they could have afforded it, but I guess it wasn’t on the cards. So, I was okay with it from that perspective. If for some reason the black and whites would not have been available, that would have been different.

'What I was going to say, to continue the analogy though, because I heard it last night actually at a screening. I was at a screening of Pandora’s Box, and that’s an all-new digital restoration done in Germany. But someone later was saying, and I’ve heard this before, "Oh, you know, I don’t like this new digital stuff. I don’t care if it was scratched. I miss that scratch that was always there". And my answer to that is that we don’t get rid of anything, we don’t destroy anything just because we’ve cleaned it up and produced a new negative. And there is a new negative of The Bridge on the River Kwai and we’ve made prints from it, and they look gorgeous. But I can always make a print off the original with all of the damage in it if somebody wants to see it again. But no one will. It’s just hard for some people to get used to'.

I’ve heard plenty of people saying that digital cinema presentations rip the soul out of a film…

'Well that can happen. I think it’s very important for those of us overseeing this work to be very careful how we use these tools because you can go too far, you can completely remove grain, you can make it as smooth looking as anything shot on hi-def today. But is that really what we want to do? I think that there’s been enough push-back from consumers buying Blu-ray that, well we learned that a long time ago from our very first releases, which was just trying to make it authentic, which we’ve tried to do ever since. Which is why the Columbia lady logo at the start of Taxi Driver is still degraded and soft looking, because that is exactly what it was in 1976 when the film was first released.

'But I think that the tools are so available and so easy to use that I’m afraid that some people just go too far. It’s just over-processing, you just have to be careful not to over-process it I think'.

Looking back over the time you’ve been doing this now, does anything stick out in your mind as the most surprising or challenging thing you’ve encountered on the restoration side of things?

'What’s interesting now is that we’re now restoring films that we previously restored 15 years ago. Easy Rider is a good example. That was kind of a famous restoration about 12 years ago. We had the filmmakers involved and we did some digital work on it too because there are two reels of negative that are long gone. And it was quite successful at the time. But to look at it now it would never be acceptable because there were things that we couldn’t do or didn’t do then. Just removing ordinary dirt, for example. The white spots that you see running through a print'.

In the near future do you expect to being going back again to redo these films for Ultra high-definition or whatever is next down the pipeline?

'Well, it is always fun to go back and do things that we couldn’t do, like that problem that just drove us crazy and we couldn’t fix photochemically, now we can. We redid Easy Rider two years ago and I managed to fix all of those things that really bothered us – and by us I mean me I mean [director of photography] László Kovács who worked closely with me on it. So it’s gratifying to be able to do that. It's all simply part of a necessary process as cinemas go digital.

'Digital projection, the move in that direction has been taking place for the last ten years. It’s slow, it costs a lot for theatres to invest, and all those issues. But I think what is the game-changer is 3D. That will ensure that everything will move to digital because you have to have that for 3D. And that’s what I see now as will change it forever. I mean, films will be shown in museums…'

On that topic, do you think that, going forward, part of the job for those overseeing the digital mastering of classic films for Blu-ray will involve 2D-to-3D conversion?

'No, I don’t really think that. I mean, it may be, but we haven’t done that. There are discussions throughout the industry about doing that, but it would have to be the right kind of film and you’d have to get the filmmaker involved. But we’re not going to take The Bridge on the River Kwai or Taxi Driver and make it 3D. That is not going to happen.

'We do have old 3D films though. And we have, I think, ten feature films, mostly from the 1950s, and two Three Stooges shorts that were shot 3D. Right now at Colorworks [Sony’s digital intermediate facility with real-time 4K grading and an end-to-end 4K pipeline] we’re actually working on those for eventual Blu-ray release and also for broadcast, because a lot of broadcasters are clamouring for 3D content. And we’re also finishing up two of the features from that period, one called The Mad Magician and one called Miss Sadie Thompson, and we’ve already finished the two Stooges shorts… all digitally so you can look at them on a 3DTV screen.

'But we can also use that to create a digital cinema version of these as well. And I’m pretty sure we’ll do that because we firmly embrace 3D and I think, and again, that’s where we’re trying to be very careful in how we do it. We’ve got Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs, which my department oversaw, and Monster House and Open Season. And there are a few others coming, like Resident Evil: Afterlife and The Green Hornet. And they start shooting the new 3D Spider-Man in December, I think. Spider-Man is one that seems tailor-made for 3D. So the new one that’s being shot has been conceived in 3D, so it’ll be quite exciting to see it. We’re just going to have to wait another year-and-a-half for it though'.

The Bridge on the River Kwai and Taxi Driver are released on Blu-ray in the UK on June 6, courtesy of Sony Pictures Home Entertainment.

|

Home Cinema Choice #351 is on sale now, featuring: Samsung S95D flagship OLED TV; Ascendo loudspeakers; Pioneer VSA-LX805 AV receiver; UST projector roundup; 2024’s summer movies; Conan 4K; and more

|